Retrofitting and Wellbeing are Key for 2021’s Pritzker Winners

The two winning architects are recognised for revitalising public housing with a creative approach to sustainable design

Mitchell Parker

24 March 2021

Houzz Editorial Staff. Home design journalist writing about cool spaces, innovative trends, breaking news, industry analysis and humor.

Houzz Editorial Staff. Home design journalist writing about cool spaces, innovative... More

“Never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform and reuse!” That’s the mantra of French architects Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, winners of the 2021 Pritzker Architecture Prize, the most prestigious award in the field.

The two are known for their focus on revitalising low-income housing complexes, choosing to modify and improve structures rather than demolish and rebuild. In 2017, for example, Lacaton and Vassal were hired to redesign a large concrete housing estate, Grand Parc in Bordeaux, France. The residents of the three blocks wanted larger flats, but didn’t want to move out during construction.

The duo, along with architects Frédéric Druot and Christophe Hutin, devised a solution to add a system of outdoor terraces over the existing structure that extended the footprint of the living rooms by adding spacious balconies with sliding glass doors. Some of the flats doubled in size. The buildings’ lifts and plumbing were also modernised, all without displacing any of the residents during construction. The project cost was one-third of the cost of demolishing and building new.

“Transformation is the opportunity of doing more and better with what is already existing,” Lacaton said in a press statement. “The demolishing is a decision of easiness and short-term. It’s a waste of many things – a waste of energy, a waste of material and a waste of history. Moreover, it has a very negative social impact.”

The two are known for their focus on revitalising low-income housing complexes, choosing to modify and improve structures rather than demolish and rebuild. In 2017, for example, Lacaton and Vassal were hired to redesign a large concrete housing estate, Grand Parc in Bordeaux, France. The residents of the three blocks wanted larger flats, but didn’t want to move out during construction.

The duo, along with architects Frédéric Druot and Christophe Hutin, devised a solution to add a system of outdoor terraces over the existing structure that extended the footprint of the living rooms by adding spacious balconies with sliding glass doors. Some of the flats doubled in size. The buildings’ lifts and plumbing were also modernised, all without displacing any of the residents during construction. The project cost was one-third of the cost of demolishing and building new.

“Transformation is the opportunity of doing more and better with what is already existing,” Lacaton said in a press statement. “The demolishing is a decision of easiness and short-term. It’s a waste of many things – a waste of energy, a waste of material and a waste of history. Moreover, it has a very negative social impact.”

Grand Parc, with Frédéric Druot and Christophe Hutin, (2017) in Bordeaux, France. All photos except where noted courtesy of Philippe Ruault.

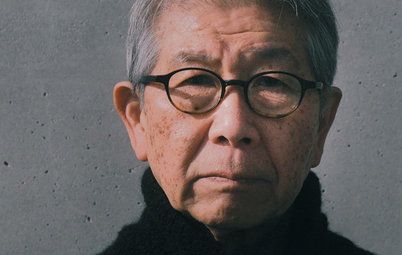

French-born Lacaton and Moroccan-born Vassal met in the late 1970s while studying architecture at the National School of Higher Studies of Architecture and Landscape Architecture in Bordeaux. Both went on to focus on urban planning.

Vassal briefly relocated to Niger, where Lacaton often visited him. The beauty of the desert landscapes juxtaposed with the severely limited resources of the population heavily influenced both architects’ life work. “Niger is one of the poorest countries in the world, and the people are so incredible, so generous, doing nearly everything with nothing, finding resources all the time, but with optimism, full of poetry and inventiveness. It was really a second school of architecture,” Vassal said in the statement.

In 1987, they established the firm Lacaton & Vassal in Paris, where they continue to work and reside.

French-born Lacaton and Moroccan-born Vassal met in the late 1970s while studying architecture at the National School of Higher Studies of Architecture and Landscape Architecture in Bordeaux. Both went on to focus on urban planning.

Vassal briefly relocated to Niger, where Lacaton often visited him. The beauty of the desert landscapes juxtaposed with the severely limited resources of the population heavily influenced both architects’ life work. “Niger is one of the poorest countries in the world, and the people are so incredible, so generous, doing nearly everything with nothing, finding resources all the time, but with optimism, full of poetry and inventiveness. It was really a second school of architecture,” Vassal said in the statement.

In 1987, they established the firm Lacaton & Vassal in Paris, where they continue to work and reside.

Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal. Photo courtesy of Laurent Chalet.

Lacaton is an associate professor of architecture and design at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and a visiting professor at Polytechnic University of Madrid, Master in Housing.

Vassal is an associate professor at Berlin University of the Arts.

Lacaton is an associate professor of architecture and design at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and a visiting professor at Polytechnic University of Madrid, Master in Housing.

Vassal is an associate professor at Berlin University of the Arts.

Grand Parc.

Here’s a look at one of the terraces added at Grand Parc. Sliding glass doors give residents flexible space that can be used for a “winter garden” or other applications.

Inexpensively increasing living space with balconies is a signature design move of Lacaton and Vassal. “There are too many demolitions of existing buildings that are not old, that still have a life in front of them, that are not out of use,” Lacaton told The New York Times. “We think that’s too big a waste of materials. If we observe carefully, if we look at things with fresh eyes, there’s always something positive to take from an existing situation.”

Here’s a look at one of the terraces added at Grand Parc. Sliding glass doors give residents flexible space that can be used for a “winter garden” or other applications.

Inexpensively increasing living space with balconies is a signature design move of Lacaton and Vassal. “There are too many demolitions of existing buildings that are not old, that still have a life in front of them, that are not out of use,” Lacaton told The New York Times. “We think that’s too big a waste of materials. If we observe carefully, if we look at things with fresh eyes, there’s always something positive to take from an existing situation.”

Grand Parc.

Here, a resident used the terrace addition to create a sun-drenched dining area off the living room. “Good architecture is open – open to life, open to enhance the freedom of anyone, where anyone can do what they need to do,” Lacaton said. “It should not be demonstrative or imposing, but it must be something familiar, useful and beautiful, with the ability to quietly support the life that will take place within it.”

Here, a resident used the terrace addition to create a sun-drenched dining area off the living room. “Good architecture is open – open to life, open to enhance the freedom of anyone, where anyone can do what they need to do,” Lacaton said. “It should not be demonstrative or imposing, but it must be something familiar, useful and beautiful, with the ability to quietly support the life that will take place within it.”

Latapie House (1993) in Floirac, France.

For the Latapie House, an early project for Lacaton and Vassal in Floirac, France, the duo updated the structure with a system of natural ventilation and solar shading that allows the residents to create adjustable microclimates.

For the Latapie House, an early project for Lacaton and Vassal in Floirac, France, the duo updated the structure with a system of natural ventilation and solar shading that allows the residents to create adjustable microclimates.

Latapie House.

On the back of the Latapie House, the architects designed an addition with retractable and transparent polycarbonate panels that create a greenhouse of sorts that increases year-round living space.

“From very early on, we studied the greenhouses of botanic gardens, with their impressive fragile plants, the beautiful light and transparency, and their ability to simply transform the outdoor climate,” Lacaton told the prize committee. “It’s an atmosphere and a feeling, and we were interested in bringing that delicacy to architecture.”

On the back of the Latapie House, the architects designed an addition with retractable and transparent polycarbonate panels that create a greenhouse of sorts that increases year-round living space.

“From very early on, we studied the greenhouses of botanic gardens, with their impressive fragile plants, the beautiful light and transparency, and their ability to simply transform the outdoor climate,” Lacaton told the prize committee. “It’s an atmosphere and a feeling, and we were interested in bringing that delicacy to architecture.”

Tour Bois le Prêtre, with Frédéric Druot, (2011) in Paris.

Before Grand Parc, Lacaton, Vassal and Druot applied a similar terrace strategy to transform another public housing project, Tour Bois le Prêtre in Paris, shown here. They removed the original concrete facade and extended the footprint by adding balconies with windows that offer unobstructed views of the city.

“Good architecture is a space where something special happens, where you want to smile just because you’re there,” Vassal said in the statement. “It’s also a relationship with the city, a relationship with what you see and a place where you are happy, where people feel well and comfortable – a space that gives emotions and pleasures.”

Before Grand Parc, Lacaton, Vassal and Druot applied a similar terrace strategy to transform another public housing project, Tour Bois le Prêtre in Paris, shown here. They removed the original concrete facade and extended the footprint by adding balconies with windows that offer unobstructed views of the city.

“Good architecture is a space where something special happens, where you want to smile just because you’re there,” Vassal said in the statement. “It’s also a relationship with the city, a relationship with what you see and a place where you are happy, where people feel well and comfortable – a space that gives emotions and pleasures.”

FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais (2013) in Dunkirk, France.

Rather than demolish a postwar shipbuilding structure at a waterfront redevelopment project, Lacaton and Vassal chose to add a near-identical building right next to it that houses galleries, offices and storage for the regional collections of contemporary art.

Rather than demolish a postwar shipbuilding structure at a waterfront redevelopment project, Lacaton and Vassal chose to add a near-identical building right next to it that houses galleries, offices and storage for the regional collections of contemporary art.

FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais.

Transparent, prefabricated materials allow views of the old building, left, from inside the new building.

“This year, more than ever, we have felt that we are part of humankind as a whole,” said Alejandro Aravena, chair of the Pritzker Architecture Prize Jury and the 2016 prize laureate. “Be it for health, political or social reasons, there is a need to build a sense of collectiveness. Like in any interconnected system, being fair to the environment, being fair to humanity, is being fair to the next generation. Lacaton and Vassal are radical in their delicacy and bold through their subtleness, balancing a respectful yet straightforward approach to the built environment.”

Transparent, prefabricated materials allow views of the old building, left, from inside the new building.

“This year, more than ever, we have felt that we are part of humankind as a whole,” said Alejandro Aravena, chair of the Pritzker Architecture Prize Jury and the 2016 prize laureate. “Be it for health, political or social reasons, there is a need to build a sense of collectiveness. Like in any interconnected system, being fair to the environment, being fair to humanity, is being fair to the next generation. Lacaton and Vassal are radical in their delicacy and bold through their subtleness, balancing a respectful yet straightforward approach to the built environment.”

FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais.

The Pritzker Prize is awarded every year to a living architect or architects for significant achievement in the field. It was established by the Pritzker family of Chicago through its Hyatt Foundation in 1979. The award consists of $100,000 (around £71,737) and a bronze medallion.

See more of Lacaton and Vassal’s work below.

The Pritzker Prize is awarded every year to a living architect or architects for significant achievement in the field. It was established by the Pritzker family of Chicago through its Hyatt Foundation in 1979. The award consists of $100,000 (around £71,737) and a bronze medallion.

See more of Lacaton and Vassal’s work below.

Related Stories

Decorating

Where Do I Start When Renovating or Redecorating My Home?

By Eva Byrne

Keen to get going on a project but not sure where to begin? Read this practical guide to getting started

Full Story

Gardens

How Do I Create a Drought-tolerant Garden?

By Kate Burt

As summers heat up, plants that need less water are increasingly desirable. Luckily, there are lots of beautiful options

Full Story

Architecture

21 Ways Designers Are Incorporating Arches Into Homes

By Kate Burt

Everywhere we look on Houzz right now, a cheeky arch pops up. How would you add this timeless architectural feature?

Full Story

Lifestyle

How to Improve the Air Quality in Your Home

Want to ensure your home environment is clean and healthy? Start by assessing the quality of your air

Full Story

Gardens

Can I Have a Lawn-free Garden That’s Kind to the Environment?

Try these tips to help you plan a garden without grass that’s still leafy and eco-friendly

Full Story

Sustainability

How Can I Incorporate Biodiversity Into My Building Project?

By Kate Burt

If you’re renovating, you have a brilliant opportunity to plan in nature-friendly touches at the outset

Full Story

Lofts

How Do I Begin a Loft Conversion?

Wondering where to start when converting your loft? Ask yourself these questions to ensure you plan well

Full Story

Living Rooms

Where Designers Would Spend and Save in a Living Room

By Cheryl F

It’s your main relaxation space, so what should you splurge or scrimp on in the living room?

Full Story

Architecture

Japan’s Riken Yamamoto Wins the 2024 Pritzker Architecture Prize

The architect is known for creating indoor-outdoor homes and buildings that foster a strong sense of community

Full Story

Working with Pros

How to Choose an Electrician

By Cheryl F

From what to ask to getting the best result possible, here’s what to know when you’re hiring an electrician

Full Story

What a wonderful ethos. Great if the U.K. could follow suite.

Congratulations to these deserving architects whose skill and philosophy benefit man and planet. If only more communities would adopt this practice.

Truly ahead of their time but feel there's finally a momentum building towards this way of thinking.