Renovating

The Controversial House that “Changed the Way We Think About Buildings”

Rivalry with Le Corbusier nearly ruined Irish designer Eileen Gray’s career, but two new films celebrate her as “The Mother of Modernism”

A villa on the Côte d’Azur, complete with priceless furniture and interior details, is one of the most significant houses of the Modernist era. Yet, after a chequered history, it was almost destroyed by squatters and, due to a long-running feud with the man generally described as “The Father of Modernism” – plus a healthy dose of 20th century sexism – its pioneering female designer was almost forgotten.

A new feature film and accompanying documentary about the life of Irish designer Eileen Gray have not only helped to complete the renovation of this important building, but aim to put the record straight about “The Mother of Modernism”.

A new feature film and accompanying documentary about the life of Irish designer Eileen Gray have not only helped to complete the renovation of this important building, but aim to put the record straight about “The Mother of Modernism”.

At the tale’s centre, though, is the more historically familiar story of a talented woman pushed aside by raging egos and male chauvinism.

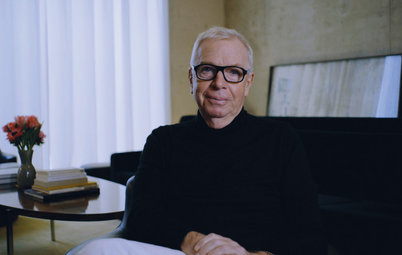

For years the house, completed in 1926 in Roquebrun-Cap-Martin on the Côte d’Azur, and named Villa E1027 (more of which shortly), was known as “Le Corbusier’s house”, as it was widely believed to be the work of the renowned Swiss-French architect, designer and painter, and he happily encouraged the misconception. In fact, the house was devised and built by Irish designer Eileen Gray, pictured here, who had a long-standing feud with Le Corbusier that almost saw Gray, also an important furniture designer, erased from the story of Modernism.

But now the life of Gray, who died in 1976 aged 98, and the impact of her design legacy, have been dramatised for the big screen in the form of a new feature film out this weekend, The Price of Desire, which aims to set the record straight.

For years the house, completed in 1926 in Roquebrun-Cap-Martin on the Côte d’Azur, and named Villa E1027 (more of which shortly), was known as “Le Corbusier’s house”, as it was widely believed to be the work of the renowned Swiss-French architect, designer and painter, and he happily encouraged the misconception. In fact, the house was devised and built by Irish designer Eileen Gray, pictured here, who had a long-standing feud with Le Corbusier that almost saw Gray, also an important furniture designer, erased from the story of Modernism.

But now the life of Gray, who died in 1976 aged 98, and the impact of her design legacy, have been dramatised for the big screen in the form of a new feature film out this weekend, The Price of Desire, which aims to set the record straight.

The film features Orla Brady as Gray (pictured here sitting on one of Gray’s designs, the Bibendum chair); Vincent Perez as Le Corbusier; Francesco Scianna in the role of her lover, Jean Badovici, the architecture critic who made Le Corbusier famous, and Alanis Morissette as another lover, Marisa Damia, a celebrated French singer of the day.

“It’s quite a mad story, isn’t it?” says Mary McGuckian, the Irish writer and director of the film. McGuckian explains she was drawn to dramatise it for its “universally applicable” theme. “[In E1027] Eileen Gray designed an extraordinary piece of modern architecture that changed the way we live in the modern world and the way we thought about buildings – and Le Corbusier couldn’t stand it,” she says.

And he’d perhaps be turning in his grave to learn that, although it’s taken almost 100 years, Gray’s reputation has recovered to the extent that one of her early designs became the most expensive 20th century chair ever to be sold at auction. It went for a jaw-dropping £19.4 million in a sale from the home of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Berge in 2009.

“It’s quite a mad story, isn’t it?” says Mary McGuckian, the Irish writer and director of the film. McGuckian explains she was drawn to dramatise it for its “universally applicable” theme. “[In E1027] Eileen Gray designed an extraordinary piece of modern architecture that changed the way we live in the modern world and the way we thought about buildings – and Le Corbusier couldn’t stand it,” she says.

And he’d perhaps be turning in his grave to learn that, although it’s taken almost 100 years, Gray’s reputation has recovered to the extent that one of her early designs became the most expensive 20th century chair ever to be sold at auction. It went for a jaw-dropping £19.4 million in a sale from the home of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Berge in 2009.

Le Corbusier (depicted here by Perez), who was both Gray’s mentor and her professional rival, was furious because – according to McGuckian and the many experts interviewed in Gray Matters, the accompanying (and fascinating) documentary on which McGuckian also worked – a woman had dared to challenge his famous Five Points of Architecture in her version of a Modernist building (she especially objected to his idea that a house was “a machine for living”; she took a much more personalised approach). And it was getting a lot of positive attention.

Among his many acts to discredit her as the designer, Le Corbusier decided the calming, cool, pale walls would look better covered in his paintings. Without Gray’s knowledge, let alone consent, he set about his style of decorating, which, like much of his work, was done “in the nip”, as McGuckian puts it, though the cinematic version has him in knitted swimming trunks.

Among his many acts to discredit her as the designer, Le Corbusier decided the calming, cool, pale walls would look better covered in his paintings. Without Gray’s knowledge, let alone consent, he set about his style of decorating, which, like much of his work, was done “in the nip”, as McGuckian puts it, though the cinematic version has him in knitted swimming trunks.

Brady and Scianna as Gray and Badovici on the terrace at Villa E1027 .

Also responsible for eroding Gray’s reputation was her philandering lover, Jean Badovici, a Romanian architect and critic, for whom she built the house. Badovici did little to correct misconceptions about the design of the house, even casually taking some of the credit himself. McGuckian continues, “Basically, the guys picked on her and she didn’t get much of a rattle at being a celebrated architect.”

It wasn’t one dramatic event or act of chauvinism that almost consigned Eileen Gray to anonymity, more, says McGuckian, “a lifetime of little omissions, acts and disrespect. Add it up over a lifetime and it’s a lot of knocking.”

The house was designed to be in harmony with its surroundings and every room has a balcony, connecting the indoors and the outdoors. The main part of this airy, cool building consists of an open-plan living area and a kitchen, bath and bedroom/study. Downstairs, there’s a guest room and maid’s quarters, plus a loo. The roof garden features an outdoor kitchen connected to the cooking space inside the house, an idea that feels very modern even today.

Villa E1027 was a code for Gray and Jean Badovici’s relationship: E for Eileen, 10 for J, the 10th letter of the alphabet, and, following this logic, 2 for B, and 7 for G.

Also responsible for eroding Gray’s reputation was her philandering lover, Jean Badovici, a Romanian architect and critic, for whom she built the house. Badovici did little to correct misconceptions about the design of the house, even casually taking some of the credit himself. McGuckian continues, “Basically, the guys picked on her and she didn’t get much of a rattle at being a celebrated architect.”

It wasn’t one dramatic event or act of chauvinism that almost consigned Eileen Gray to anonymity, more, says McGuckian, “a lifetime of little omissions, acts and disrespect. Add it up over a lifetime and it’s a lot of knocking.”

The house was designed to be in harmony with its surroundings and every room has a balcony, connecting the indoors and the outdoors. The main part of this airy, cool building consists of an open-plan living area and a kitchen, bath and bedroom/study. Downstairs, there’s a guest room and maid’s quarters, plus a loo. The roof garden features an outdoor kitchen connected to the cooking space inside the house, an idea that feels very modern even today.

Villa E1027 was a code for Gray and Jean Badovici’s relationship: E for Eileen, 10 for J, the 10th letter of the alphabet, and, following this logic, 2 for B, and 7 for G.

Villa E1027, pictured here, overlooks the Bay of Monaco, and Gray chose the plot for its beautiful views across the Mediterranean.

A potted history is tricky, since, as already outlined, there are so many twists and turns in the story of this house. But in short, according to McGuckian’s research, Gray, as an unmarried woman and foreigner, couldn’t legally own the house, so it was put into Badovici’s name. But they intended to live in it together, and the issue became more significant after the couple split.

When Badovici died, before transferring ownership, the house went to his only living relative – a nun in Romania. As a nun, she was unable to own property and so the Romanian state took possession and auctioned the house. It almost went to Aristotle Onassis, but Le Corbusier persuaded a wealthy friend to buy it (she was responsible for hurling much of Eileen Gray’s furniture out of the window as it wasn’t to her taste).

The apparently drug-fuelled murder of a gardener at the property was almost the last in a long line of dramas there, although, as recently as the early 1990s, the house was taken over by squatters. Against all odds, E1027 had remained reasonably well preserved until then, but at that point, says McGuckian, “it was really destroyed. It was a very unlucky house.”

A potted history is tricky, since, as already outlined, there are so many twists and turns in the story of this house. But in short, according to McGuckian’s research, Gray, as an unmarried woman and foreigner, couldn’t legally own the house, so it was put into Badovici’s name. But they intended to live in it together, and the issue became more significant after the couple split.

When Badovici died, before transferring ownership, the house went to his only living relative – a nun in Romania. As a nun, she was unable to own property and so the Romanian state took possession and auctioned the house. It almost went to Aristotle Onassis, but Le Corbusier persuaded a wealthy friend to buy it (she was responsible for hurling much of Eileen Gray’s furniture out of the window as it wasn’t to her taste).

The apparently drug-fuelled murder of a gardener at the property was almost the last in a long line of dramas there, although, as recently as the early 1990s, the house was taken over by squatters. Against all odds, E1027 had remained reasonably well preserved until then, but at that point, says McGuckian, “it was really destroyed. It was a very unlucky house.”

Not so now. In the early 2000s, restoration work began with the state-appointed architecte en chef et inspecteur général des monuments historiques, Pierre-Antoine Gatier.

In 2014, McGuckian’s team got involved in some elements of the restoration as part of the agreement that they could shoot there. The director was astonished at the level of detail in Gray’s design. “She designed every last detail – and everything was completely tailored to suit Badovici, who liked to work, play sport and entertain. There was lots of storage for his sports equipment. He also liked to work lying down, so there was a daybed, which could also be a guest bed.” There was also a desk that could become a dining table with the addition of a cork top, to stop the clattering of cutlery disturbing guests.

“This was very modern at the time,” says McGuckian. “I have the idea that if you find a classic piece of furniture in Ikea or Muji or Habitat, you can probably trace it back to Eileen Gray.

“The interior and the exterior were all part of the architecture of the house. These days when we describe somebody designing a villa for someone in this way, we call it domestic architecture. This was more than that – it was intimate architecture – every need of her ‘client’ was catered for.”

In 2014, McGuckian’s team got involved in some elements of the restoration as part of the agreement that they could shoot there. The director was astonished at the level of detail in Gray’s design. “She designed every last detail – and everything was completely tailored to suit Badovici, who liked to work, play sport and entertain. There was lots of storage for his sports equipment. He also liked to work lying down, so there was a daybed, which could also be a guest bed.” There was also a desk that could become a dining table with the addition of a cork top, to stop the clattering of cutlery disturbing guests.

“This was very modern at the time,” says McGuckian. “I have the idea that if you find a classic piece of furniture in Ikea or Muji or Habitat, you can probably trace it back to Eileen Gray.

“The interior and the exterior were all part of the architecture of the house. These days when we describe somebody designing a villa for someone in this way, we call it domestic architecture. This was more than that – it was intimate architecture – every need of her ‘client’ was catered for.”

Gray’s adjustable table, still in production today, continues the flexible theme. It can be lowered to work as a coffee table or raised for eating breakfast. She is said to have designed it for her sister, who liked to breakfast in bed.

Check out how to find the right bedside table for you

Check out how to find the right bedside table for you

Gray’s Transat chair, one of which is in E1027, is still in production today and could originally be used as both an interior or exterior chair.

“There were 171 separate designs above the usual builder’s finish in the house,” says McGuckian. “There was built-in furniture, freestanding pieces, wall hangings, kitchen furniture, soft furnishings, these clever double reversible door hinges, hat racks, modules for gramophones, and a bulb in a capsule that looks like something designed today. Her designs were just so enduring.”

The Price of Desire is released in select UK and Irish cinemas from May 27, 2016.

TELL US…

Share your thoughts on this story in the Comments below.

“There were 171 separate designs above the usual builder’s finish in the house,” says McGuckian. “There was built-in furniture, freestanding pieces, wall hangings, kitchen furniture, soft furnishings, these clever double reversible door hinges, hat racks, modules for gramophones, and a bulb in a capsule that looks like something designed today. Her designs were just so enduring.”

The Price of Desire is released in select UK and Irish cinemas from May 27, 2016.

TELL US…

Share your thoughts on this story in the Comments below.

In juicy headlines, the story of the house and its designer and various inhabitants, which started in the 1920s and continued for most of that century, involves much drama, from a bisexual love triangle to the building’s Nazi occupation during the war; a lively auction to sell the house, involving the Communist state of Romania and Aristotle Onassis, to a murder in the building’s garden; priceless pieces of Modernist furniture being hurled out of windows, to angry graffiti painted onto the walls by a naked Le Corbusier, aka “The Father of Modernism” (who, years later, drowned in the sea in front of the house).